Thanks to the diligent and hard work of Clonehenge, we have a really good understanding of Stonehenge replicas and pastiches from across the world. There are a surprisingly large number of these, over 100 (!!), from complete and partial replications of the original monument itself, to installations and structures inspired by those (in)famous trilithons in a range of different materials. “Clonehenge covers replicas and models of Stonehenge from the sublime to the ridiculous” is the very fair claim made on the blog site that curates all of this information. I’ve been thinking about Stonehenge replicas in the past few years with Rebecca Younger, and others have been researching the phenomenon, such as cultural geographer Tim Edensor who has written about the controversial Achill Henge in Ireland (Edensor and Smith 2020). So when I was holidaying in northern Iceland in the summer of 2023, I just had to take the opportunity to visit the most northerly franchise of Stonehenge – Arctic Henge!

OK, as Clonehenge notes, this is not an actual replica of Stonehenge. “Not in the sense we’ve been using for that term until now, but at winter solstice the resemblance comes to the fore. Like Stonehenge they seem to forge a bond between us as entities of the landscape and the dance of the bodies in the dome above us”. So this megalithic structure takes inspiration from aspects of that weird stone circle in Wiltshire, has trilithons of a sort and uses the -henge suffix.

By way of digression before we get into the detail of Arctic Henge, this reminds me that in the summer of 2009 Jan and I visited Stonehenge Aoteroa, a replica of Stonehenge to the north of Wellington in New Zealand.

Rather like the Sighthill stone circle in Glasgow, this monument is very much astronomically focused, although there are also embedded within its architecture the presentation of Māori stories about the skies and constellations.

This makes me wonder if Jan and I are two of the few people in the world who have achieved the hat-trick of visiting the most northerly and the most southerly Stonehenge replicas in the world as well as the original Stonehenge. This should become a thing except for the appalling carbon footprint of doing it. Bad me.

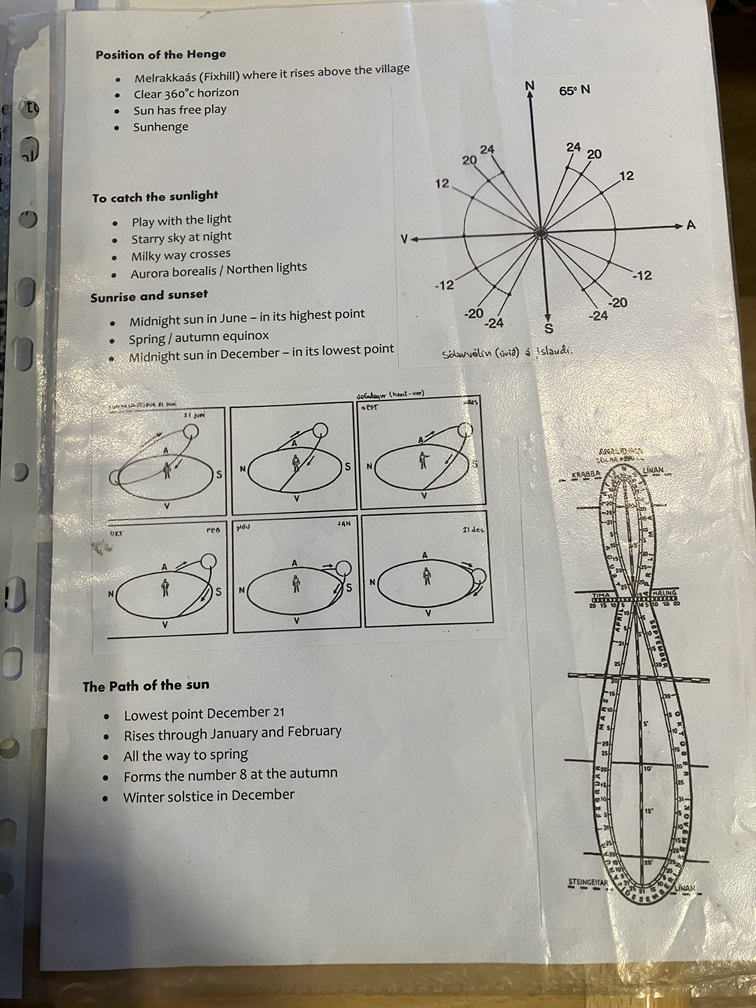

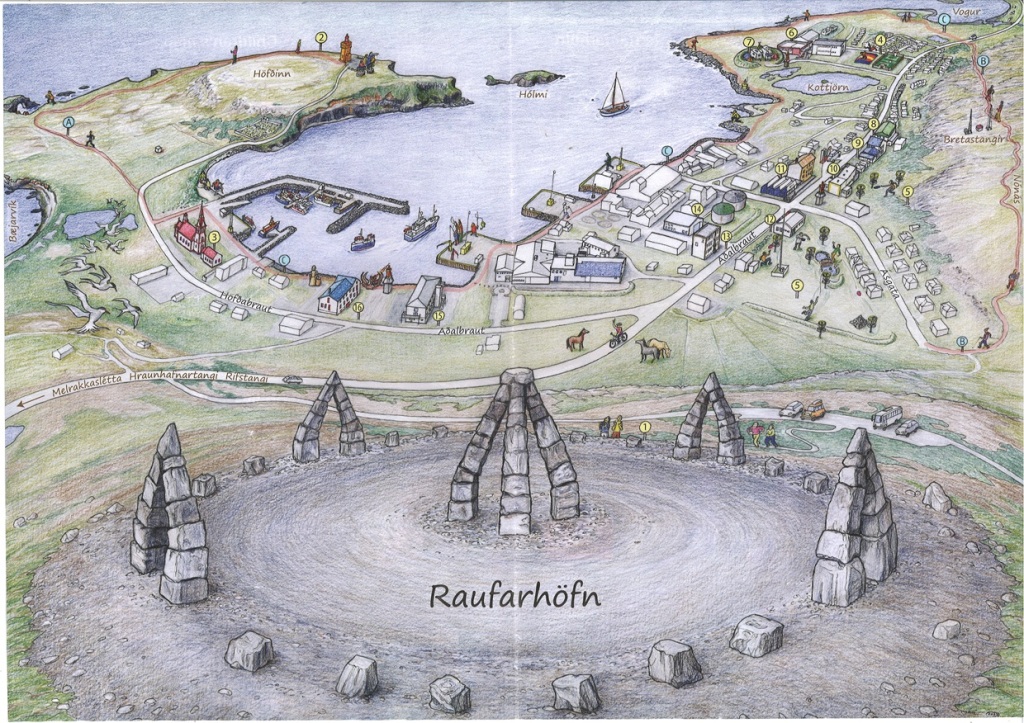

Anyway, back to Arctic Henge, a remarkable work in progress that appears to be a valiant attempt to get more people to visit a rather remote corner of Iceland, the small town of Raufarhöfn, the most northerly town and within 8km of the actual Arctic circle.

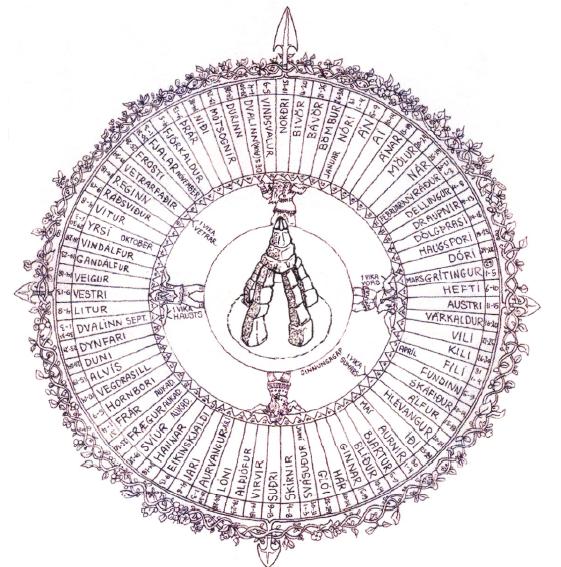

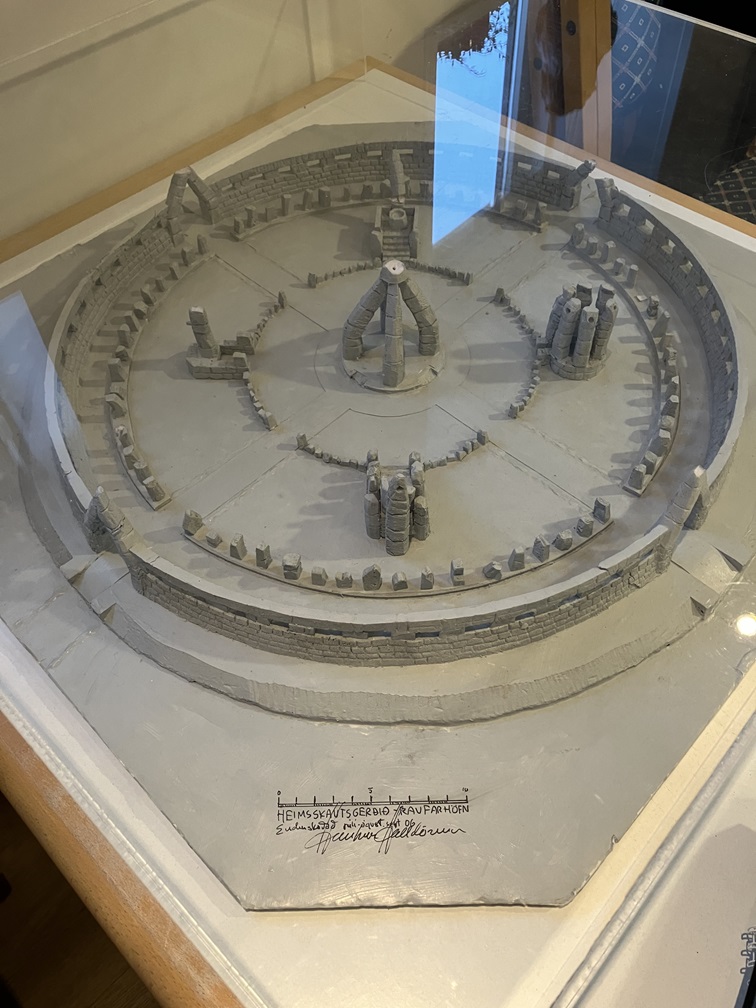

The monument – also known as Heimskautsgerðið – was the vision of the late Erlingur Thoroddsen, working with artist Haukur Halldórsson, with the idea emerging in the 1990s and construction beginning in 2004. The monument is tied up in complex Icelandic dwarf symbology and mythology, as well as having solstice alignments built into its form. The whole story can be found here, and so I won’t go into huge amounts of detail here, as the vision and plans for this monument are a bit bamboozling.

The monument is connected to 72 dwarves, each allocated a different five days of the year, with “the four cardinal dwarves of Norse mythology, Austri, Norðri, Suðri and Vestri … befittingly face their namesake, east, north, south and west”. There are a whole host of other dwarves, none of them called Sneezy, and the website for the monument leaves it ambiguous as to what this all actually means although everyone should be able to work out who their dwarf is based on birthdate I think, a nice gimmick that deserves merch. There are also allusions to ‘endless horizons’ (true although it was foggy all of the time we were there), the midnight sun, and solstices – the circle being characterised as a ‘sun dial’.

The monument is some 50m in diameter, and is dominated by four enormous pairs of pillars which form ‘gates’ with an even bigger central setting. I assume they are made of blocks of lava. These are the most recognisable elements of Arctic Henge, often shown in photos with the Northern Lights playing in the background.

The biggest of these sits in the centre of the circle, formed of four angular arches. This facilitates the four site lines across the monuments so that the monument can be used to view solstice events through the legs of the gates as it were. It also has a wee tiny hole in the middle in the top.

As noted already, this is a work in progress. Money seems to have dried up and crowdfunding is being used to try and move things along. You can donate here, apparently the project only needs 1.3 million dollars to be completed. There is no doubt that a lot of work needs to be done when one sees the final vision for this place.

During our visit we stayed at the nearby Hotel Northern Lights (Hótel Norðurljós), and in the lobby there were plans and even a model of the Henge which hinted at Thoroddsen’s vision.

In fact he owned the hotel and so in part I suppose this was to drum up business for this rather austere property – and perhaps to provide entertainment as THERE ARE NO TELEVISIONS IN THE ROOMS!! He told Meet the North in an interview not long before he passed away that he wanted to reverse the fortunes of this small town that has been in steady decline since the collapse of the herring industry in the 1960s. I love people like this – visionaries who ignore conventional logic to make their dream happen. The replica Stonehenge world has a lot of folk like this.

Images online confirm the scale of what this monument might one day look like, such as this one from the Iceland Dream website (original source unknown but it is clearly based on the model pictured above).

When (if, rather than when works better I fear) finished it will include a circle of 68 small standing stone – the non-cardinal dwarves with weird names – and the official website for the project suggests that the whole 10m high central edifice would one day be topped with a “cut prism-glass that splits up the sunlight unto the primary colors [sic]”. I guess that explains the wee hole.

It is all very tantalising! Here’s another visualisation from Bensozia blog, again artist unknown.

And this image, reproduced by Clonehenge, was once on the official website (no more) and shows other proposed weird internal features:

This, then, is an epic project in a crazy place and I suppose a parallel might be the never-ending construction of the Sagrada Família in Barcelona, although Thoroddsen himself saw a closer parallel – Stonehenge itself. He told Meet the North that, “It took 1,500 years to finish Stonehenge,” and in this sense, he is correct. Because Stonehenge was always a work in progress. It was never finished in the conventional sense of what we mean by that word, and a series of eccentric and impractical visionaries probably drove the project on crowdsourcing labour and big standing stones. But in all likelihood whatever the final, final vision might have been was unachievable.

Visiting the site is in itself a powerful experience regardless of the weather. The huge gate structures dwarf (no pun intended) and overlook the village as you drive towards it from the south.

As noted already, when we visited, there was a lot of low cloud and that sort of unpleasant cold rain slapped our faces as we left the car to inspect a frankly glorious information panel in a lay by near the site.

From there we walked up to the site, a few hundred metres away up a gentle slope, some of it with a path. The first thing that struck me was the massive car park that has been constructed here, which literally is visible from space if you count google earth as space. This seems to me the very definition of a white elephant, but perhaps aspirational would be a better expression. There is no harm, I suppose, in planning for some future problem parking scenario. It is difficult to see this ever being full. We visited in the middle of summer and there was no-one else there.

And yes, the site is a work in progress, and there was evidence for quite recent activity around the boardwalk that takes one from the massive car park up to the monument itself. Some elements seemed fairly freshly worked on, and there were a lot of blue pipes knocking about.

Once up on the site, it proved to be endlessly photogenic as one might imagine. There were stunning views and juxtapositions in almost all directions, the dramatic megaliths working perfectly in harmony with the grey sky and the Fargo-esque town next door. The lack of visitors in contrast to actual Stonehenge was refreshing.

We were also able to appreciate some of the less commonly photographed elements of the monument, such as a rickle of stones that ran around its circumference, and random piles of stone. There is a wonderful organic emergent quality to this place, and despites its final form being pre-destined like the movement of the sun, when you are in this place anything seems possible.

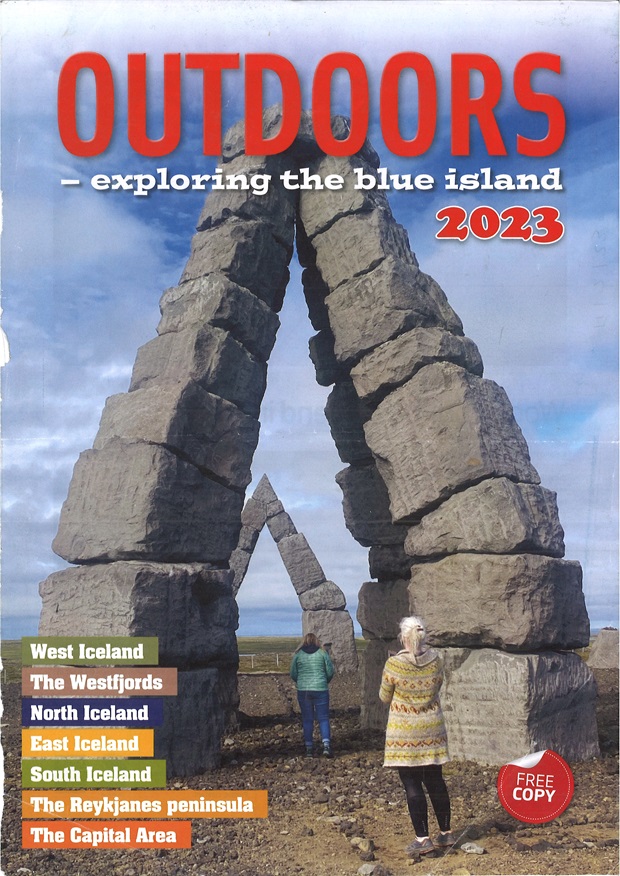

And there is no doubt that Arctic Henge is working hard to put Raufarhöfn on the map. The images of the gates (sometimes with northern lights) are well on the way to becoming iconic, a synecdoche for the monument as a whole (as with the Stonehenge trilithons). They appear in advertising for instance such as the cover of this brochure I picked up in Akureyri. And entry is free – I wonder if there are any plans to change this in the future?

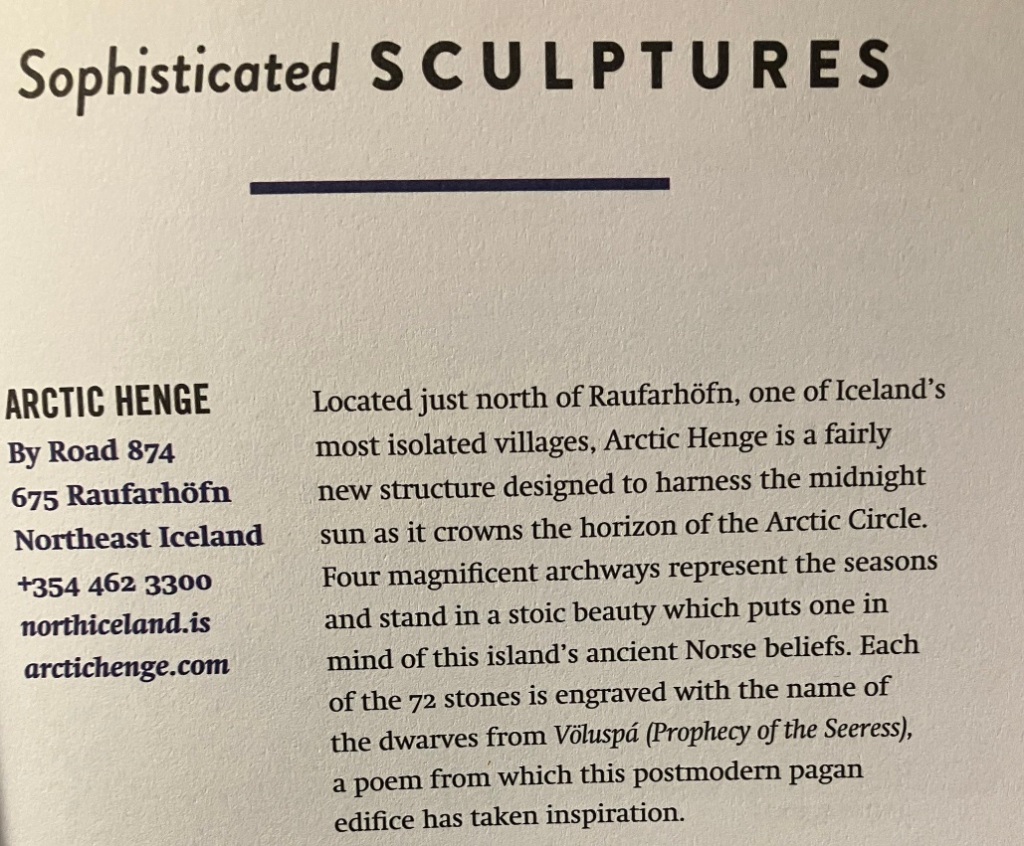

And of course the monument features heavily in travel books and guides, such as the Atlas Obscura, and below there is an extract from a glossy but rather content-light guide book called Hidden Iceland (Michael Chapman, 2022); the description suggests the author did not actually visit. Then there is TripAdvisor (‘#1 of 7 things to do in Raufarhöfn’) with 45 reviews at the time of writing (27-01-23), only five of them Poor (“Bizarre pile of rocks” which is very similar to a few reviews I’ve read of actual Stonehenge!). This is a monument that is only going to get more visits in the future with the north coastal route of Iceland (Arctic Coast Way) now being marketed as an off-the-beaten track version of the more familiar A1 ring road route. It might even be reachable from cruise ships, which brings mixed blessings to megaliths in places like Orkney. The downside is that it is challenging to get to without a car.

Some folk will make the trek, and there they will find a relatively new megalithic monument in harmony with its environment and its community. This lovely A3 poster advertising the facilities of Raufarhöfn was freely available from the hotel reception and suggests, like many megalithic monuments, that it can add to a sense of pride in a place.

It reframes the view that I shared earlier, with the stone structures lying behind the town. Here, we have the town viewed almost through a megalithic prism, with the promise of an actual prism to come in the future.

It is not Stonehenge. It doesn’t look like Stonehenge. But it uses the -henge brand both for marketing but also to give a sense of what this place might be about. Some visitors might be left disappointed by the lack of Stonehengeiness of this place, while others will see it for what it is – a magical vision in stone.

It is not easy to get here, but by goodness it is worth it!

NB This is my third Iceland blog post – here are the others if you are interested:

Nothing BC (UP blog post 62)

An archaeology of artificial geysers (UP blog post 161)

Sources and acknowledgements: I would firstly like to state my admiration of Clonehenge as a project and concept, such a valuable and amazing resource! I would also like to thank Rebecca Younger, we have had a lot of henge conversations over the years. Sorry I got to Arctic Henge before you!! Photos with no credits were taken by Jan Brophy and I.

Source mentioned: Edensor, T & Smith, TSJ 2020 Commemorating economic crisis at a liminal site: memory, creativity and dissent at Achill Henge, Ireland. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 38.3, 567-84 (if you want a pdf of this paper, email me! kenny.brophy@glasgow.ac.uk – as it is not open access).