What should we make of an archaeological site that does not exist in official records of archaeological sites? Without the seal of approval from the authorities, inclusion in the list of record of such sites, is there some doubt as to the authenticity of such a site? And in the void of archaeological engagement, what myths and tales might emerge for those who know the site better than anyone – dogwalkers, nighttime imbibers, those in the know, those who spend time at the site but don’t even know it is there? Is there a value in such urban urban prehistory myths?

In this post I want to consider these issues of archaeological invisibility through examining the unusual case of an abstract prehistoric rock-art site that in local walking routes is known as Site G. This is the story of how this site is gradually been reclaimed from obscurity by local people and school children, and highlights the enduring potential of prehistoric sites in urban places to have significance and value even in the least promising of situations. So let me transport you to the green belt border zone between Bonnybridge and Denny, in central Scotland.

Caught in the jaws of urbanisation, increasingly hemmed in by housing expansion, compressed in scope in the vice-like grip of progress, horizons narrowing, the Chacefield Wood rock-art site is a true survivor. It is a genuinely ancient site, a relic of a bygone age, a carved rock outcrop that increasingly only has the solace of the quiet trees that stand around it to rely on, timber guardians of an ancient secret that is mostly the preserve of local people, pram-pushers, lockdown walkers. Located within proximity to two motorways and the intersection that connects them, this place is better connected than most rock-art sites because of these arterial routes to big cities – Glasgow, Edinburgh, Stirling, Perth. On a map even these roads take on a jaw-like quality, closing in on the carvings which are situated in a green tongue of woodland. Yet this connectedness, being on a route, has done little to benefit the profile of this this site which appears – until recently – to have been ignored by all archaeological recording processes in Scotland, left to the warm embrace of local knowledge, lore, and just about on a walking trail in a rapidly diminishing green space.

Surprisingly, little has ever been written about this lonely outcrop. It is not documented in the National Record of the Historic Environment in Scotland (with canmore its online portal). It is therefore not even officially an archaeological site, just a thing of conjecture. Is it real? If it is real surely it would be recorded somewhere officially? This is a place that is doubted in its authenticity, and a google search does little to breed confidence due to some mostly fuzzy photos of a rock in the shadows.

Yet this is also a rock-art site that appears in the marketing of leisure by the local council, Falkirk. In a leaflet entitled Discover the Paths in and around Bonnybridge, that can be found online, the rock-art site appears as part of the Drove Loan to Chacefield Wood walk.

Marked in a general map of the area showing historic sites of interest with a G (although the location is not really made that clear due to the scale of the map and the size of the G) the site in described thus:

Chacefield Wood Cup and Ring Marks: The term “cup and ring carving” describes a range of rock carved symbols that are found mainly in northern Europe, although similar carvings occur in other countries around the world. In Britain the carvings are estimated to be around 4000 – 5000 years old which dates them to the Neolithic and Bronze ages. The purpose and meaning of the symbols is unclear. Many of the rock carvings are sited near or on cairns and burial mounds, linking the symbols with death, ancestors and an afterlife.

A very small image of part of a cup-and-ring mark is also included in this leaflet, a tantalising glimpse.

A more detailed map of the walk does not show the actual location of the rock-art site, perhaps inviting the intrepid explorer to spot the outcrop from the path, or preserving the enigmatic mystique of this place.

The site is on the database map for Scotland’s Rock-art Project which is the step before becoming an official site in the national record, although as far as I can tell the site has not been formally visited yet (they are nearing the end of the recording phased of the project). This at least gives the exact location of the site and a good grid reference (the site is ScRAP ID 3085), but the record form remains incomplete and there are no photos or 3D models in the system yet. The site remains, for the time being, unverified. Still, official recognition is getting closer, so perhaps this is a real site after all.

Abstract prehistoric rock-art is having something of a renaissance in archaeology. Her excellent recent book, Design and Connectivity, Joana Valdez-Tullett (of Scotland’s Rock-art Project) places sites such as Chacefield into a broader Atlantic rock-art tradition, which sort of reflects what the Bonnybridge walk leaflet was hinting at. Suddenly Site G is looking a whole lot more significant, and its splendid isolation (it is the only site of its type in Falkirk Council area) is to extent mitigated by spiritual and cultural connections that have routes that expand beyond the motorway network of central Scotland. Plus, no rock-art site is alone that has friends….

Photos online (there are very few) show a humble site, a rather rough boulder with a set of at least three deeply-incised cup-and-ring mark symbols in a line on the upper part of the rock, with assorted cupmarks, some of which may be natural features that have been augmented or included in the pattern. On some images there appears to be the remnants of graffiti painted onto the stone in red, ghostly letters rather like those you would see painted above an old shop.

With this basic information in mind, I went on a series of visits to this rock-art site during the summer of 2020, after a tip off that it existed from a friend, Michelle, who lives nearby. I was somewhat confused why this site was not documented in canmore, despite the fact that it looked legit. On my first visit I recorded a short bit of film on my mobile phone about my visit which has since been used for a teaching session in a local school. After parking nearby, and with only a vague sense of where the carved stones might be, the chase was on!

I followed a busy A road from the cul-de-sac where I parked, which was resplendent with front gardens containing boulders and standing stones, a good start. As I walked past, a postman emerged from his van and dropped several parcels into the gutter, perhaps surprised by my sense of purpose. I strode on, my walking style enlivened by the presence of a good old metal red and white 1m ranging rod, which would act as photographic scale, but was currently employed as a walking stick.

The trail into the woods was a good one, and I followed the main track, all the while tapping my metal pole into the ground with a regular metallic ping like a demented woodpecker. Looking from side to side in the time-honoured fashion, I eventually spotted a suspiciously conspicuous outcrop about 50m to the south of the path.

I walked over with a renewed sense of purpose and sure enough, this was Site G! The site was actually spread across two adjoining outcrops, with one zone of cup-and-ring marks (north stone), the other just cupmarks (south) although on later visits I came to suspect there were rings here too. Simply staring at cup-and-ring marks and tracing their depth with your fingers often seems to conjure up additional aspects of the assemblage, sometimes real, other times imagined.

There is no doubt in my mind that these are genuinely prehistoric markings, deeply incised, in a location that if there had been no trees would have had quite dramatic views of the surrounding landscape. Now the site is dominated by the hum of the nearby M876 and the murmur of dogwalkers talking to one another or on phones. The smooth rolling of pram wheels was another background aspect to my first visit, utter normality as I perched on a stone covered in 5,000 year old markings.

The stones were covered in a carpet of leaves, prematurely autumnal, as if the seasons had sped up in this location, rushing towards winter and the inhabitation of stone hollows with white crisp frost. Time can bend at prehistoric sites and nature dances according to the whim of the power of stone.

There were clear signs that this is a place that is used. Just hidden enough to be off the main trail, but not dark and dingy enough to be a truly secret spot, there was detritus all around of drinking, and the sociable eating of crisps and sweets. Smashed glass concentrated around the southern extent of the outcrop, with some fragments nestling inside the cupmarks themselves. These represented a kaleidoscope of possibilities, their sharp shards and angles contrasting with the smooth flow of the ancient symbols carved into the stone.

There were also a few instances of graffiti on the northern outcrop, near and perhaps overlapping with the cups and rings. Letters of indeterminate form, in red, white, blue, were carelessly daubed across the flow of the cup-and-ring marks, overwritten in paint. Defiant messages shouted into the void, forgotten slogans, passing fancies, fading youth, melting into the past.

My first visit ended walking back to the car, a spring in my step, happy to have visited the best rock-art site in the Falkirk area, guided by a corridor of lush vegetation.

While I was at Site G I noticed that there was a horrible looking green pool of water between the path and the outcrops, full of bottles, half-submerged plastic bags, slick with an oily surface of glossy green rainbows. Even as I was standing at the rock-art two people passed by and one of them pointed to this pond saying ‘That’s stinkin’. I found out later from Michelle that this revolting pool is known to some locally as Shrek’s Swamp.

With this local hydrological phenomenon for orientation, Michelle was able to positively identify the rock-art where in the past she was not so sure. Her kids had a great time playing count the cupmarks!

Being a teacher, the next obvious thing to happen was that Site G, this unofficial, largely unrecognised rock-art site, was to become the focus for some teaching sessions at the fairly local secondary school where she works, with Jan (aka Mrs Urban Prehistorian). As it happens, they had both taught classes for the People and Society course around the Cochno Stone rock-art site, so this was the perfect opportunity to talk about prehistoric rock-art using a local example.

One thing that interested me was the locality next to Shrek’s Swamp and the potential for narratives and stories to emerge that connected the rock-art and this local landmark. Myths and stories about rock-art are something that Joana Valdez-Tullett has been keen to explore and celebrate, and here we had a chance to myth-make about the Chacefield rock-art site, spinning stories about the symbols and how they were carved in the same way as children playing on the Cochno Stone must have done, and Ludovic Mann did with his paints. So the People and Society class were challenged to come up with their own tall tales linking the cup-and-ring marks and Shrek’s Swamp.

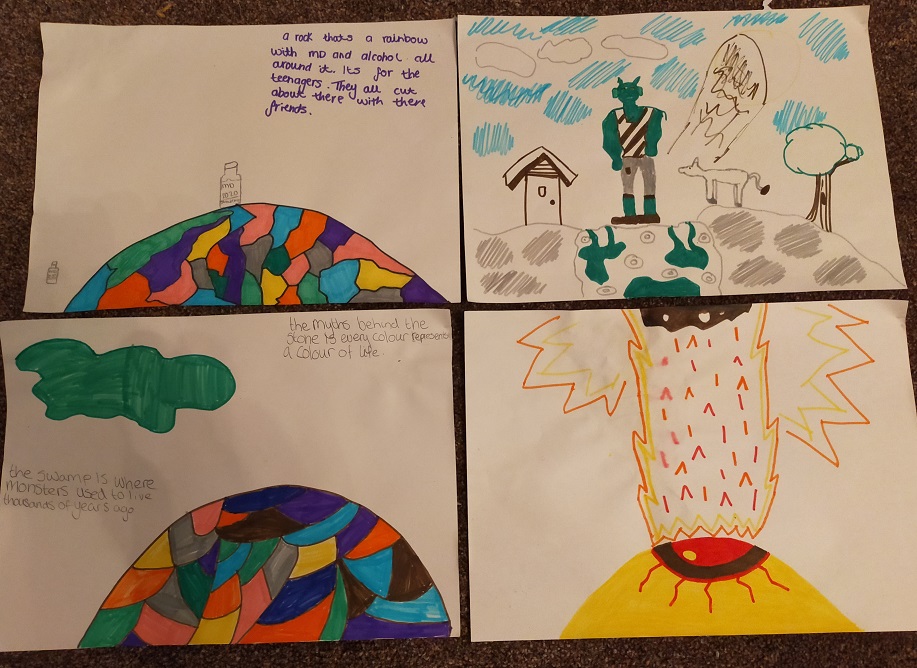

I recorded some video about this with Jan, and then the kids were set to work, after learning all about prehistoric rock-art and the Cochno Stone in the classroom. The results were amazing!

These are stories that reflect the current reality of this rock-art outcrop: ‘Its for the teenagers. They all cut about there with there friends’. But there are also stories of escapism and magic that transcend the grey blandness of this stone: ‘The myths behind the stone is every colour represents a colour of life’.

Some stories not pictured above link the creation of the symbols on the stone to the Shrek universe: ‘Donkey wants to kill everyone in the world and so he plans the whole thing on the rock…’, while another tale suggests that the rock was so shaped to allow rain water to gather on the stone so Shrek and donkey can drink from it each morning…’and now it is for people to sit on’.

These fantastical tales are a product of a class that was unusually engaged by this series of classes, so I am told, and mirrors what people have always done about the places that they live and the ancient megaliths they encounter within them. They spin tall tales to tell their children, or let their imagination run riot to the amusement of adults, all to explain the mysterious away. More often than not such stories contain an element of truth, or at least a whole lot of insight. In the past it is not such a stretch to imagine that cupmarked stones were places that people hung about, that water gathered in the hollows, that the carvings had meaning to those who made them, that the symbols reflected the colours of life.

This might not be getting the Chacefield Woods rock-art site a place in the national record of monuments – but this a valuable form of validation.

In the absence of archaeologists trying to make sense of Site G, then why not let these children, some of whom already were aware of the rocks and swamp, having seen them, present their version of events? Who are we to say they are wrong? Will these tales be consulted when the modest story of this rock-art site is told by archaeologists when Chacefield is finally given the official recognition of a canmore entry, a photogrammetry model and completed recording form in the ScRAP database? Probably not. But in the minds of local people, dog walkers, teenagers cutting about with one another, we cannot stop colourful stories being told, and why should we want to. There is more to Site G than meets the eye.

Sources and acknowledgements: I would like to thank Michelle for telling me about this site, and for Jan and Michelle for making this part of their teaching, in what I know is precious classroom time. Thanks to the pupils who took part, who were happy for their artwork to be featured in my post. Jan and Michelle also provided some of the photos in this post.

I would also like to thank Joana Valdez-Tullett and Maye Hoole (both Historic Environment Scotland) for engaging with me about this site. Joana’s book, referred to above, is:

Valdez-Tullett, J 2019 Design and connectivity: The case of Atlantic rock-art. BAR Publishing.

Thanks also to Kenny Baxter aka @SporadicArtist for allowing me permission to reproduce his photograph of the site.