>> the statue got me high <<

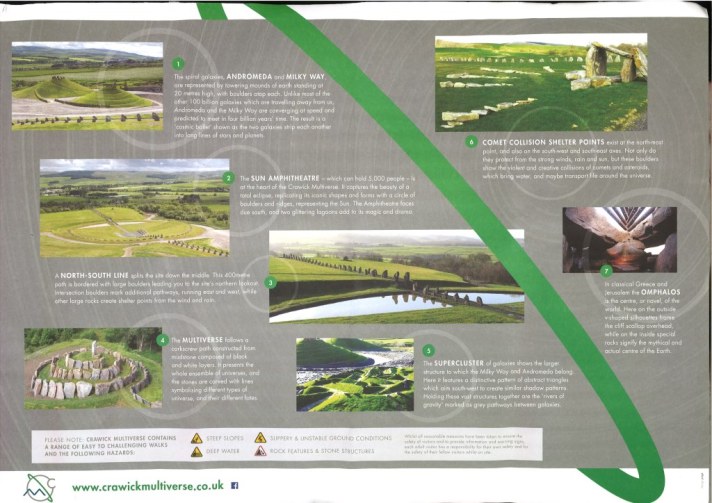

A megalithic landscape has been created in an abandoned open cast mine on the edge of the town of Sanquhar, Dumfries and Galloway. It is the Crawick Multiverse. Opened to the public in June 2015, and ten years in the planning and making, this ambitious landform was created by the artist Charles Jencks and funded by the Richard Scott (aka the Duke of Buccleuch). The complex of stone circles, stone rows, megaliths and mounds represents grand cosmic themes:

This world-class landscape art design links the themes of space, astronomy and cosmology, creating a truly inspiring landmark that will appeal to everyone from art enthusiasts and scientists to the wider community.

This is a truly impressive place on an awesome scale, and I have now visited it twice: once when construction was well underway in June 2014, and again in February 2016. The scale and ambition of the venture, and the aspiration to revitalise a ruined post-industrial landscape, are impressive. But yet I can’t help having reservations. There is a curious lack of acknowledgement that the created forms have prehistoric origins, with the cosmic meanings always to the fore. And I also wonder how much the local community will benefit from the Crawick Multiverse.

I am a great proponent of the value and utility of constructing megalithic monuments today and tomorrow, rather than seeing such structures as just belonging to the ancient past – but in doing so we also need to give a good deal of thought about who will benefit and the messages megaliths can convey. The messages I got at Crawick were decidedly ambiguous as soon as I stepped back from the initial shock and awe of the experience. This post has allowed me to explore my surprisingly ambivalent reaction to a place – a landscape – that I feel I should love, but can’t.

>> the stone, it called to me <<

Our minibus wound along the A76, travelling from New Cumnock towards Sanquhar. To the north the land was scarred by huge opencast mines, the earth being emptied of its resources in a quite brutal fashion, although in this post-coal age these scars in the land are about to become post-industrial. Gavin MacGregor was leading the field trip, and I was driving, with our destination, at that point, shrouded in mystery, as Gavin had intended all along.

Just before we got to Sanquhar, and as we passed an old military hospital to our right, Gavin indicated we turn left and I did so, steering the deep blue bus and our passengers up a minor road and beneath a railway bridge. On the horizon to our left was an old mining bing, and atop this sat several standing stones, which I was fairly sure were new additions to the skyline. As we heading up an even smaller road into what appeared to be an active quarry site, we were greeted by dozens of similar standing stones in various arrangements, as well as several large yellow diggers rolling back and forth in a dusty beige desert. This working site, this quarry, was punctuated by grey dusty zones and unkempt green sprouting grass, while bing-drumlins and spoilheap-aretes loomed over us to the north and west. Some of these anthropomorphically generated landforms had been further altered, with paths and cairns scraped from the land, with a purpose as yet unclear.

Leading off from the area where we parked up the minibus was an avenue of megaliths, an arrow-straight line hundreds of metres long flanked on both sides by standing stones: scores of them.

These straddled an amphitheatre of Classical form, suggesting a chronological and spatial mash-up was being created, while dolmen and standing stones in various arrangements emerged from the side of the avenue. There seemed to be hundreds of megaliths, disappearing off into an invisible point in the distance, an impossible arrangement that defied the material realities of what is just ‘some art in an old mine’. The illusion of infinity was one that was first attempted at Carnac, Brittany, in the Neolithic where thousands of standing stones set in painfully glorious rows go on for ever and ever, transcending time, offering the maddening possibility of counting the stones, reaching the end of the monument, which of course can never happen, really. Walking along such avenues is not about walking from A to B but from travelling from Now to Then. Or Then to Now if you are able to make the return journey, which not everyone can. To have one’s mind blown is not such a bad thing when it is being blown by a million megaliths. And my first experience of the Multiverse was on the verge of doing just that.

Actually: this is Carnac. This is Silbury Hill. This is Croft Moraig. This is Bargrennan. This is amazing! Or is it? The contrived nature of this construction site left me queasy, megaliths arranged with clinical precision, where even the casually leant standing stone was an act of proficient design. The fragmented standing stones, shedding pieces of themselves into cairns around their base, was a convenient organic effect, cultivated and left un-checked. The heavy machinery creeping around me had touched and lifted standing stones in a transactional way that could not replicate the pull of the rope, the touch of many hands. The act of translating the vision of the artist and the desire of the wealthy landowner into reshaping the land from industry to art was far too tidy and clean for my liking. Prehistory was dirty, dangerous, unpredictable, improvised. Heavy industry was dirty, dangerous, unpredictable, improvised. There was little sense of any of these qualities at the nascent Multiverse, which was when I first visited in effect incarnate and not yet fully realised and so I left my concerns to one side and took lots of photos in the dying light.

>> the monument of granite sent a beam into my eye <<

Approximately 2,000 boulders have been used to create the Crawick Multiverse site

The Sun amphitheatre can hold 5,000 spectators

The north-south line comprises approximately 300 boulders

The site spans approximately 55 acres

The Northpoint provides a 20-mile 360 degree panoramic view

Around 300 boulders were used to create the Multiverse landform [source]

>> it took my hand, it killed me, and it turned me to the sky <<

This landscape of megaliths and mounds represents the multiverse, a concept borrowed from the wilder edges of physics, which refers to the theory that there are multiple universes that exist parallel to one another. Every element of the Crawick Multiverse is a designed element, the vision of the artist made material – and very much in the spirit of other landforms by Jencks such as The Garden of Cosmic Speculation near Dumfries. There is a real sense of order about this place, a narrative to be followed, changes underfoot and the choreography of bodily movement signalling a transition into a new aspect of the cosmos and a new set of meanings. There are boundaries and divisions evident everywhere: a division horizontally into ‘four ecologies’ (grassland, mountains, water gorge, desert); a division vertically into a ‘high road’ and a ‘low road’; the classification of every element of the complex into named zones and monuments (the North-South path, the Amphitheatre, the Supercluster). This is stylised and rule-bound landscape: made of materials from a singularity of concentrated industrial destruction in an unusually creative Big Bang.

A map to the stars is provided for visitors to help make sense of this four-dimensional experience and this includes more detailed interpretations of the key elements of the landscape for the benefit of the visitor, as none of this is really self-evident. The artist as god, create now, explain later, leave a little mystery, and don’t walk on the grass while you’re at it.

Descriptions of each element emphasise the cosmological and astronomical inspiration for Jencks’s landscape installation. The Supercluster for instance represents ‘the forming of our universe and its place within the cosmos’ with an abstract jigsaw of triangular mounds held together by the ‘rivers of gravity’. The Sun Amphitheatre is all about the ‘beauty of a total eclipse’ while three Comet Shelter Points can be found across the site. At the northern end of the complex sits an artificial mound topped with a spiral setting of large standing stones, some with lines carved upon them. This megalith is the Multiverse itself, ‘the whole ensemble of universes’.

The Belvedere Finger sites atop the highest point of the site, on another mound with another spiral path to the top. It is capped by a spectacular plinth upon which a viewing board – the Northpoint Sign – is placed, and it affords views right down the North-South megalith avenue. This is an eccentric plinth – a lectern – a music stand holding a semi-mythical manuscript mapping the surrounding landscape. This is surely also the control panel for a spaceship with information encoded with our origins, found deep within the coal, to help us read the land. The sacred geometry of the ancient past exposed: ‘Cairns’, ‘River Nith Barrow’, ‘Sean Caer Fort’, ‘St Brides Church’. The bones of the land.

Has this spaceship just landed, or is it about to take off? Are these our instructions to achieve escape velocity: or colonise planet earth?

>> A rock that spoke a word (an animated mineral, it can be heard) <<

Position yourself at the control panel of a megalithic spaceship that landed on planet earth –

Landed here, thousands of years ago, when we were still prehistoric –

Adjust yourself –

Calibrate –

Close the air locks –

Set the controls to transcend time –

Place your hand upon the lever and pull back –

Pull back hard –

Warp speed, warp space, warp time –

Find the booster –

Turn on the thruster –

Feel the throb of the stones beneath your feet –

The energy beneath your feet –

Un-docking procedures initiated –

Into the multiverse.

>> (and now I see the things the stone has shown to me) <<

There is another modern megalithic monument nearby, just outside the town of Dalmellington in East Ayrshire. Erected for the millennium, ‘The Standing Stones of dael meallain tuinn’ is a monument to mining, a marker recognising that this is land that has been worked by people for thousands of years.

The use of rocks for standing stones here is not about the cosmos, but about the earth itself, looking to the ground, not the sky. Consisting of an arc of seven standing stones set on a crescent-shaped mound the name of this monument means ‘the meeting place at the mound with the motte’. The invocation of a motte here in the monument name hints that this is a central point, a place of justice, a parliament.

Behind the stones sits Pennyvenie coal bing, another industrial Silbury Hill. And like the Multiverse Silbury Hills, these standing stones and the fabric of this monument are made from industrial debris, offered up by the earth. But unlike the Multiverse, this simple, austere monument captures much more poignantly the heavy industry that preceded it. This is a thoroughly rooted monument, with connections as deep as a seam of coal.

This megalith sits at the entrance road to an open cast mine / quarry, the last and ugly vestiges of the coal industry that once dominated the Doon Valley. But access to the standing stones appears not to be encouraged, restricted by a locked gate and warning signs, and so detaching the stones from the communities which they represent. Because the seven stones represent seven mining settlements – Dalmellington, Bellsbank, Burnton, Craigmark, Benquhat, Pennyvenie, Waterside – a Proclaimers-like roll call of towns and villages entangled with heavy industry and the extraction of minerals from the earth, villages and towns forever associated with our changing and voracious energy demands.

Heavy industry created communities but also caused dislocation and ensured the disempowerment of those communities: the locked gate, the entrance fee, maintain this status quo.

>> They pale before the monolith that towers over me <<

My second visit to the Crawick Multiverse, 20 months after the first, was a very different affair. Again, I was on a fieldtrip and again I was driving a minibus with Gavin taking the lead, but this time the minibus was silver. We arrived in the car park for the Multiverse around 3.30pm with blue skies and the orange setting sun casting our long shadows onto the footpaths and fences. It was interesting to note that the Multiverse still doesn’t merit a Brown Sign all of its own on the A76, almost as if it is still on probation as a proper tourist attraction.

We were introduced to the landscape by one of the staff and he handed out A3 colour maps (see above) which included brief descriptions of the key elements of the Multiverse. The trappings of a fully open tourist attraction are beginning to emerge where before there had been a just been a rough quarry road: fences, gates, car park, noticeboards and a portaloo were in place, with the focal being being a temporary ticket office in the form of a portacabin where it is possible to purchase mugs and postcards.

We followed one of the two entry pathways and began to head uphill, skirting round a bing, before emerging out onto an escarpment which we followed right to the top. In places this was very steep and muddy. (There are ongoing drainage problems which appear not have been fully resolved although on our arrival it was hinted that an elaborate drainage system had been developed.) We passed a setting of four large standing stones, and as the path up the side of the bing became steeper, so we got increasingly spectacular views to the south and west over an awesome landscape of standing stones and mounds.

Towards the top of the ridge we encountered the mound with the huge white viewing map on it (the Belvedere Finger), and wound our way up to the top of this on the spiralling pathway, stopping to take in views from time to time, and look down into a large round hole, filled with water and its own spiral path, the Void Shelter according to our maps. At the centre of this vortex was a flat megalith.

From these high points of the site it was easy to appreciate the major changes here since our last visit almost two years previously.

Beyond the top, one of the Comet Shelters was closed, and the path was roped off in places due to mud and erosion. It’s almost as if the site is trying to return to its previous (pre-)industrial form, defying the careful shaping and health-and-safety requirements of such a visitor attraction. We passed the spiralling Multiverse, essentially a Brittonic megalith, and headed to the spiritual core of this landscape, the Omphalos.

This was very different from other elements of the complex. It consisted of large red sandstone blocks set into a megalithic chamber, with an austere iron gate, while an iron grid also overlay the top, making entry almost impossible, and certainly not permitted. The map describes this place as the Omphalos, the ‘centre or navel of the world’ – the interior megaliths are ‘special rocks’ representing the ‘mythical or actual centre of the world’. The unusual restriction of access, red rocks and harsh metal elements gave this a very different feel from the rest of the installation. As we stood here, the setting sun turned this megalithic wall and chamber ahead of us into a deep orange to blood red, and we were afforded fine views along the North-South path. From A to B, past to present, looking through megaliths to a railway viaduct and Sanquhar resting below.

>> The stone it calls to you (you can’t refuse to do the things it tells you to) <<

What do I think about it all? Superficially it is awesome, with the scale and ambition matching some of the great building projects of prehistory. But this also leads me to deeper reflection on the curious lack of prehistory within this land art. Perhaps it is so in–your-face and explicit that the site consists of hundreds of standing stones and several megalithic arrangements that it need not be mentioned. But there appears to be an almost perverse desire to dress up the meaning and utility of this place in cosmic terms, deliberately (for it can only be deliberate) making little or nothing of the quite obvious Neolithic elements that abound in this old quarry. This is weird because visitors do latch on to the prehistoric parallels quite readily: Trip Adviser users have called it ‘Stonehenge 2’, ‘a modern Stonehenge’ and ‘a modern ancient site’. An FT journalist who wrote about the Multiverse (link below) noted: “The great avenue, pointing towards a nearby viaduct and more distant hills, has the cryptic simplicity of a Neolithic alignment”. And multiple allusions to megaliths, Stonehenge, Carnac and so on can be found online.

What is going on here? Why does the published material related to the Multiverse almost entirely ignore the prehistoric appearance of this place, and focus instead on the industry and local landscape (a little) and the cosmos (a lot)? It is almost as if there is a desire to reach for the heavens and the future, rather than back into the past. Yet this is a landscape that has depth and has been occupied for thousands of years. This is celebrated on the noticeboard for the Dalmellington seven standing stone monument which says:

‘For over 6000 years there have been settlements around the Loch Doon area, and in particular the Doon Valley’.

The Multiverse is not the first megalithic construction in this landscape and it will not doubt not be the last. The past, present and future are entangled in stone in this place, mined and quarried to make monuments, mined and quarried to extract coal and other minerals, mined and quarried to pluck large rocks from the pit to repurpose as modern megaliths. All these actions are about power, about the economy, about people living and working together. The Multiverse represents another part of the biography of this land – but so far, just one small part, standing on the shoulders of megalithic giants and the labour of mining communities.

>> And what they found was just a statue standing where the statue got me high <<

What it the Multiverse for? To what end has something like £1 million been spent (the figure widely quoted in the media)? Who benefits?

There is no doubt that the Multiverse is a timely intervention, largely economic and social, although it has also addressed a literal hole in the landscape. An article on Crawick that appeared in the Financial Times suggests that motivations included improving the quality of landscape that had been essentially sucked dry and then abandoned by an opencast mining company, much to the dismay of local people. Another motivation was as prosaic:

‘to help revive the local economy, hit hard by the demise of the mining industry and by the fact that the region is, in tourism terms, a backwater: the Crawick Multiverse could be a much-needed draw.’

There is also no doubt a degree of a very wealthy landowner using a chunk of his money philanthropically to support the arts. Charles Jencks himself has said, “This work of land art, created primarily from earth and bounders on the site, celebrated the surrounding Scottish countryside and its landmarks, looking outwards and back in time”. This could be viewed as a generous act of largesse, or a rich man’s privilege, depending on your perspective. It is probably a bit of both.

But what do local people actually think about this place? What value for money do they feel has been squeezed from a millionaire’s spare million quid? There was an aspiration early in the process to give free access to local people I believe, although I can’t find any evidence that this has actually been implemented. Certainly, it is free to visit on foot after hours when the car park is closed – but this applies to everyone and anyone, not just locals. (Ironically, Buccleuch recently courted minor controversy with a plan to charge for access to another of the Duke’s estates, Dalkeith Country Park in the evenings.) I am not sure how many jobs have been created either – were the staff working for the Estate anyway, or have new posts been created? As yet, it is too early to assess how strong visitor numbers are, or how many of those visitors also pop into town and have lunch or spend money in local shops. Mosaics on site created with local schoolchildren (see photo above), and talk of school and educational visits, suggest another benefit which could emerge through time.

Perhaps if the Crawick Multiverse can genuinely catalyse economic regeneration, create jobs and revitalise interest in this forgotten corner of Scotland, then the gesture of the Duke and the creative genius of Jencks will be vindicated. But if this turns out to be art for arts sake, an industrial-scale folly, visited by those with cars, excluding large chunks of the population, an elitist attraction, then perhaps something else should have been done with this huge hole and the money to help the local community.

Sources and acknowledgements: the title of this post and the subheadings are all taken from the They Might be Giants 1992 song The statue got me high (from the album Apollo 18). Information about the Crawick Multiverse came from their website (including the quote near the start of the post and the list of stats that make up the third section of this post) and the map handed out to visitors (a few extracts of which are included in the post). Thanks to the Estate for allowing us access to the Multiverse during construction, and informative conversations with staff on both visits, and thanks also to Gavin for facilitating the visit in 2014. The opening ceremony image was sourced from a BBC story about this event, source link in caption. Finally, thanks to all of those who joined me on those two fieldtrips, chats during walks around the Multiverse helped shaped my own thoughts.

Perhaps this is being over critical, but given that it’s supposed to be based on cosmology, it’s just a shame that they didn’t align any of the structures or stone alignments to the sun or moon. Although there are many prehistoric monuments out there that are solar/lunar aligned, no one on any official level promotes this.

Hi, I don’t think you are being unfair in the sense that they could have built in an alignment or two for the public to enjoy. On the other hand I get the sense the whole complex is a fit for the landscape where it is and how it is aligned. On you other point I do think you are being unfair to professional archaeologists here – there is wide consensus that some alignments on the sun and moon were part of how prehistoric monuments worked, but there are debates about level of accuracy and how important these connections might have been to the monument builders…

Kenny

Hi Kenny, On reading your text I was wondering what archaeo-astronomy data the academics you mention are using. I might be wrong, apart for Thom’s and Ruggles surveys, I don’t think there is much in the way of fieldwork, but maybe that’s just because I’m out the academic loop. I have had a few papers published, but apart from a few archaeologists who have used some of my surveys, most of the comments I’ve received are derisive. One I survey a site, I go back again and photograph the events, and to date I have about 300 pictures of the sun or moon rising or setting in line with monuments. I don’t think that this is anything to do with astronomy, but with Neolithic and Bronze Age beliefs. I do have another paper being published soon on the solar lunar orientations of the Orkney-Cromarty and Clava passage cairns, but I doubt this will change anything. I’m well aware of the accuracy arguments, and while I don’t agree with Thom and Mackie’s notch ideas, I’m beginning to find some evidence of simple geometry. I met you a number of years ago when you were digging a burial cairn at Loch Yarrow’s and I got very interesting results from the stone rows to the south. I can send the info if you are interested. Douglas Scott.