Between 5th and 22nd September 2016, the Cochno Stone was revealed, recorded and reburied. For 10 days the complete surface of the stone was completely exposed and visitors were able to see the rock-art and the paint and the graffiti on this magnificent rock dome for the first time in 51 years. Analysis of the data we collected during this period is ongoing and we will continue to disseminate results and images as we go forward (follow @cochnostone and see the project outline). In the meantime, I am using my blog to publish here the summary report of the archaeological results of the work to date so that everyone who wants to find out what we were up to can find out. A brief account of the preliminary 2015 phase of excavation can be found in an earlier blog post.

REVEALING THE COCHNO STONE

Phase 2 excavation and digital recording summary report

Summary

The Cochno Stone, West Dunbartonshire, is one of the most extensive and remarkable prehistoric rock-art panels in Britain. It was however buried by the authorities in 1965 to protect it from ‘vandalism’ associated with visitors and encroaching urbanisation. A proposal has been developed to uncover the Stone, and 3D scan it, to allow detailed study of the stone, and an exact replica to be created and placed in the landscape near where the original site is. Two seasons of excavation have now been carried out to enable an assessment of the condition of the Cochno Stone and gather high quality digital and photographic data for future analysis and replication of the Stone. This summary account is an archaeological report on the main 2016 season of excavation of the Cochno Stone, where the Stone was completely uncovered up to the edge of the modern retaining dry stone wall, recorded, and then buried once again. Key discoveries include the survival of paint on the surface of the stone from the 1930s, the extent of modern graffiti, and the recovery of very high resolution digital data and photographic imagery of the complete surface of the stone. The third phase of the project, the creation of the replica and legacy activities, will follow on from phase 2 when funding is in place.

The Cochno Stone: a brief history and background

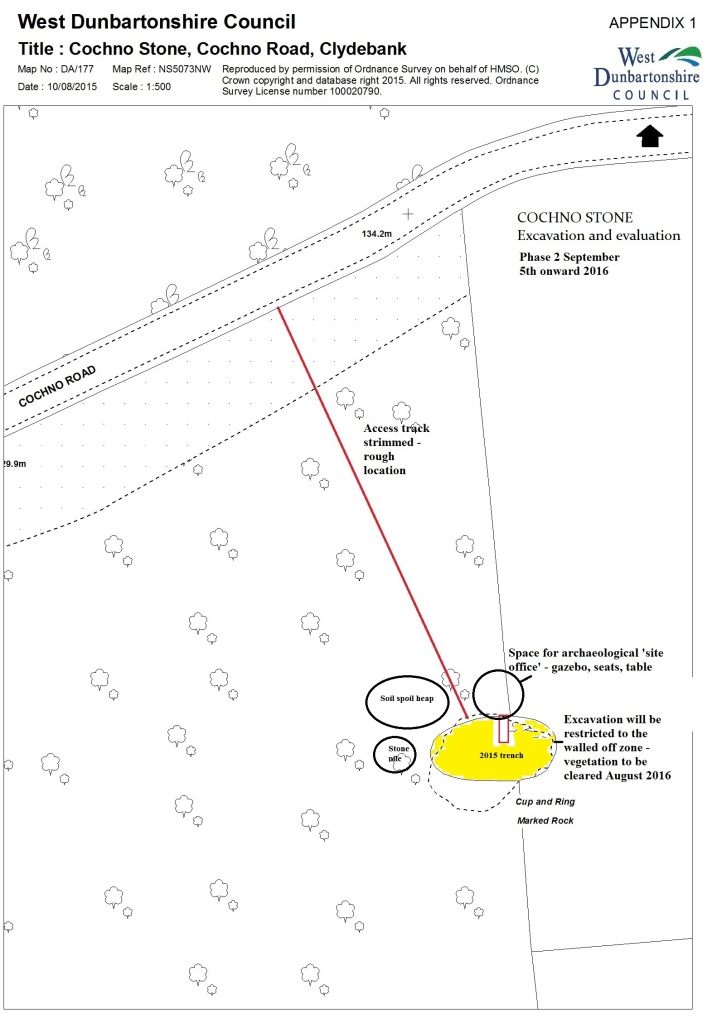

The Cochno Stone (aka The Druid’s Stone and Whitehill 1; NMRS number NS57SW 32; NGR NS 5045 7388), West Dunbartonshire, is located at the foot of the Kilpatrick Hills on the north-western edge of Glasgow, in an urban park in Faifley, a housing estate on the north side of Clydebank (Figure 1). It is one of up to 17 panels of rock-art in this area (Morris 1981, 123-4) but by far the most extensive. Indeed, the Cochno Stone is one of the largest and most complex prehistoric rock-art sites in Britain. The zone of rock-art on this large outcrop measures some 15m by 8m, and is covered in scores of cup-marks, cup-and-rings marks, spirals and other unusual motifs. The surface is dome-like, sloping sharply to the south and west, less so to the north, and is a ‘gritstone’ or sandstone; the most concentrated zones of rock-art are on top of the dome and on the southern and western slopes of the outcrop. The stone location has extensive views to the south and over the Clyde valley and when fully exposed in prehistory would have been a localised high point.

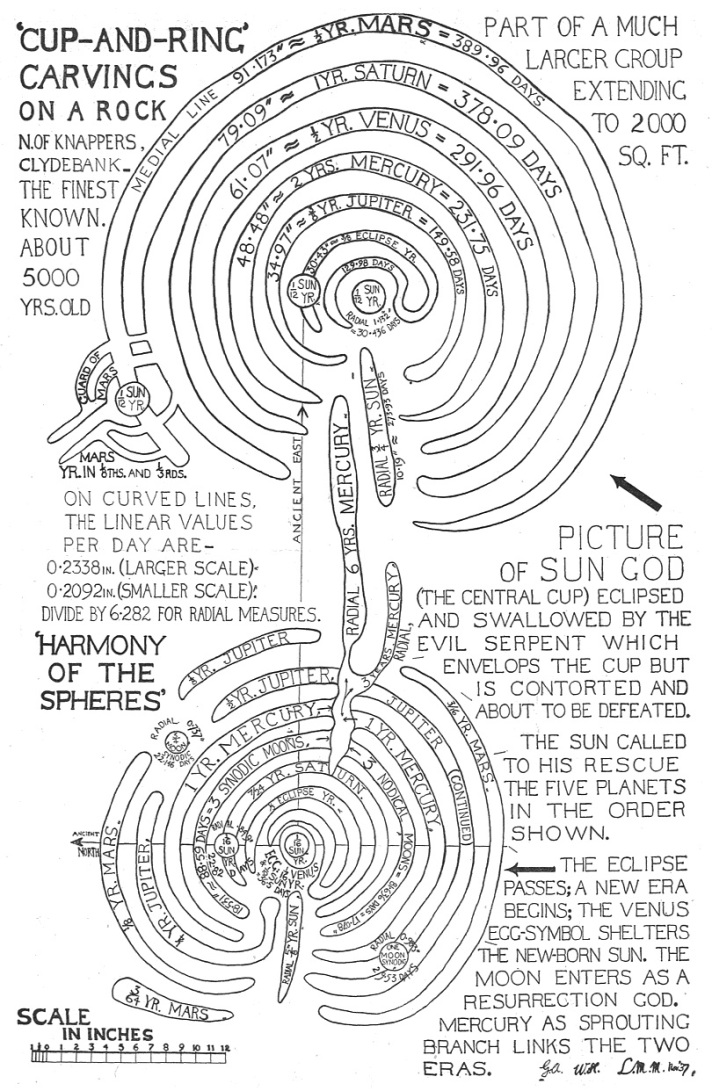

The Stone was first documented by the Rev James Harvey of Duntocher, who came across the incised outcrop in 1885. Harvey explored beneath the turf around the Cochno Stone and some other examples in the area to test their extent, and then published his results in volume 23 of the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland (PSAS). He included a detailed description of a profusion of classic and unusual rock-art motifs across a large sandstone block (which he called Stone A). Soon after this John Bruce produced a review of other rock-art sites in the region which was published in PSAS in 1896, and here he included a full sketch of the Cochno Stone by W. A. Donnelly (Figure 2). Donnelly’s drawing was the basis for Ronald Morris’s own sketch plan (see Figure 4) although Morris was dismissive of its reliability based on his own observations of photographs of the Stone (when Morris visited the Stone was already buried (1981, 124).)

The Stone subsequently became the focus for archaeological attention in the mid-1930s when Ludovic Maclellan Mann took an interest in it, located as it was relatively close to the remarkable Knappers prehistoric site on what is now Great Western Road (Mann 1937a, 1937b). Mann infamously ‘painted’ the motifs to make them clearer, apparently for a visit of the Glasgow Archaeological Society in 1937 (Ritchie 2002, 51). Mann added his own speculative grid as well (see Figure 12) and it likely that other motifs he painted onto the rock were fanciful on his part. Some black and white photos of the Stone from this time suggest more than one colour was used. Mann believed the Cochno Stone was used to help predict eclipses and ‘celebrate the defeat of the eclipse-causing monster’ (Mann 1937b, 14, and see below).

The Cochno Stone was buried in 1965 under a thick layer of soil to protect the stone surface from being walked on by visitors and graffiti and paint being added to the stone, a decision made by the Ministry of Works and Ancient Monument Board early that year. Records held in the Scotland’s National Archives show that from the 1930s onwards the two landowners of the Cochno Stone (it is located on a historic land boundary) were becoming concerned about damage to the rock surface, a process that seems to have accelerated after the site was publicised by Ludovic Mann. A dry-stone wall with a style had already been constructed on and around the stone before the 1930s in part to discourage visitors and demarcate the stone location, and this was used as a boundary and container for the soil that was dumped on top of the stone. But this was deemed insufficient protection for the Cochno Stone and it was buried beneath up to 1m of soil.

This remained the case until the current project was proposed in 2014. Revealing the Cochno Stone has as a long term the objectives the creation of an exact facsimile of the Cochno Stone to be placed near the real thing. To realise this ambition, a staged process has been adopted.

- Trial excavation [completed September 2015]

- Full-scale exposure of the Cochno Stone and 3D scanning [completed September 2016]

- Post-excavation analysis of data (ongoing, late 2016 into 2017)

- Production of a 1:1 facsimile of the stone, placement in landscape and legacy activities [funding now being sought for this phase of the project]

Phase 1 (2015) summary (link for full report in introduction to this blog post)

A small-scale excavation was undertaken in September 2015 to assess the current condition of the Stone, and to inform a potentially larger clearance of the surface of the Stone in the future. A small trench, 4m by 1m, was opened by hand on the northern side of the Cochno Stone location. This revealed that the Stone is buried beneath between 0.5m and 0.7m depth of clay-silt-loam, and that the dry-stone wall surrounding the Stone was partially destroyed during burial. Seven deeply incised cup-marks were recorded, three with rings around them, and the Stone was shown to be in good condition, albeit soft in character. Evidence for vandalism was also found including graffiti and melted plastic; samples were taken of the latter. At the end of the excavation, the trench was backfilled. The excavation allowed several observations and recommendations for future work to be made. These included:

- The Cochno Stone remains in good condition despite its burial, but the stone surface is soft so care must be taken when cleaning the stone surface;

- It is likely existing drawings of the Cochno Stone are inaccurate in terms of content and certainly in scale;

- The surface of the stone will have extensive modern graffiti on it;

- The wall surrounding the stone appears to have been pushed over during stone burial but its lower courses and foundations remain extant.

Phase 2 – Excavation and 3D scanning September 2016

The second phase of excavation of the Cochno Stone ran from 5th to 22nd September 2016. This consisted of three phases of work:

| 5th to 12th September | Removing topsoil and cleaning the Cochno Stone by machine, water and using hand tools |

| 13th to 19th September | Laser scanning, photogrammetry, archaeological recording, hi-spy and ongoing light cleaning |

| 20th to 22nd September | Reburial of the Cochno Stone, by hand on the 20th, followed by two days of machine work |

The area of the Cochno Stone bounded by the dry-stone wall was chosen as the focus of all the work: an area measuring 15.2m E-W by 8.6m N-S. The outcrop continues beyond this zone but almost no rock-art has been found on these fringes, and these zones of the rock outcrop were in any case not buried in 1965. The overburden was removed by a closely monitored mini-digger with a mini-dumper ensuring spoil was taken well clear of the site, with large stones removed by hand and placed on a separate spoil heap. Once the digger had cleared to within 10 to 15cm of the surface of the stone, the remainder of the spoil was removed by hand using plastic shovels and scoops to avoid damage to the stone surface. All large stones were also removed by hand so that the digger could not scrape them along the surface of the Cochno Stone. Once completed, the Stone was then carefully washed down by a firefighter using a hose, to ensure slow but safe cleaning. The site was also brushed with soft hand brushes and sponges after this, and it was only permissible to walk on site with socks on or specially designated clean plastic shoes. A stone conservator, Richard Salmon, was on site at all times and able to advise on these matters.

Phase 2 results

The following research questions and objectives underpinned the Phase 2 full exposure of the Cochno stone: here provisional answers to these questions have also been presented, and some key findings will be discussed in more depth below.

| No. | Research question | Provisional observation | Implications / further research |

| 1.1 | What condition is the Cochno Stone in? | Very good condition with no obvious decline due to burial | Management – stone burial stable in short term even with no geotextile breathable layer |

| 1.2 | Has the overlying topsoil had a detrimental effect on the stone? | No obvious problems associated with soil lying on the stone surface. Black areas may be staining? | Investigate nature of the black areas – paint or staining? |

| 1.3 | Could any damage be reversed or stopped? | Not applicable although we have no way of assessing long-term stability | Geotextile laid on the stone surface before re-burial at the end of the excavation |

| 1.4 | Has the collapsed wall caused any damage to the fringe of the stone? | No damage of any note was recorded although large stones were found lying on the surface | No stones were laid directly on the Cochno Stone surface during backfilling |

| 2.1 | How clearly visible are the motifs? | The carved symbols vary from very clear to very faint | Analysis of data will reveal all visible symbols and some not apparent with the naked eye |

| 2.2 | How accurate are the old drawings we have? | They appear to contain most of the symbols but there are clear issues of scale and spatial arrangement | New plan to be produced using survey data

Comparison with older drawings and analysis |

| 3.1 | Can phasing be identified amidst the rock-art? | Yes, some cup-and-rings marks overlay one another, and symbols had different depths and wear evident

Different methods of pecking evident |

Analysis of data but also adoption of MacKie’s methodology adopted at Greenland (MacKie & Davis 1988-89)

Scan will enable analysis of pecking methods employed |

| 4.1 | Does the rock-art run beneath or continue beyond the boundary wall? | Not as far as we could tell although our SMC conditions set out that we could not remove the wall. Where one section was removed for drainage, no rock-art was found | Outcrop beyond dry-stone wall to be re-examined for any motifs other than those recorded by Morris |

| 4.2 | How is the wall attached to the stone? | The wall was laid directly on the surface of the Cochno Stone with no binding as far as we could tell | The wall remains have been left in situ as it has a historic connection to the Cochno Stone |

| 5.1 | Is there any evidence for activity contemporary with the rock-art panel being in use? | Nothing was found and the surface of the stone had no cracks | Future investigation of the fringes of the outcrop e.g. downslope, worth doing |

| 6.1 | Do any traces of Ludovic Mann’s paint remain? | Yes, we found extensive evidence for his paint work including use of various colours: white, yellow, green, blue, red | Samples taken of paint

Digital reconstruction of how the stone would have looked in 1937 to be undertaken Research into Mann’s work |

| 6.2 | Were any objects associated with the 1965 burial of the stone found? | Nothing we can directly connect to the burial, but we did find two marbles, two coins and a Red Cross medal on the stone surface / wall base | Analysis of topsoil finds

Identification and conservation of coins and medal |

| 7.1 | How extensive was the graffiti on the surface of the Cochno stone? | Graffiti was concentrated on the southern and western sides of the stone, and for the most part did not overlap with prehistoric rock-art. Mostly names and dates

Several possible ‘modern’ cup-and-ring marks were identified |

All graffiti was photographed and logged

Attempts made to contact those who did it Analysis of content, location, form of graffiti to be undertaken |

| 7.2 | How extensive was visitor damage to the surface of the Cochno stone? | Nothing obvious on the surface of the stone

One zone near the centre of the stone may have been bleached by a fire |

Data analysis should reveal wear patterns e.g. near the style into the walled area

Investigation of ‘fire’ area |

| 7.3 | Was anything found adhering to the surface of the stone? | Nothing additional to what was found in 2015 | Melted plastic to be analysed |

Reburial

At the end of the fieldwork, the Cochno Stone was reburied. We covered the surface of the Stone with a breathable geotextile layer, initially weighed down with rocks carefully placed by hand. A layer some 10cm thick of soil was placed back on the Stone by hand, with care taken to ensure no large stones was amongst this material. Finally, the remainder of the overburden was placed onto the Stone by a machine, and the mini-digger landscaped the site back to its initial form.

Archaeological recording

During the cleaning of the overburden, we collected a sample of the objects found within the deposits on top of the Stone. Once the surface of the Stone had been completely revealed and cleaned, detailed scale photography was undertaken of the Stone, as well as sampling of various paint deposits and other materials adhering to the surface . We did not draw the Stone as a new plan will be generated from the digital and photogrammetry data collected.

Small finds: During the cleaning of the Cochno Stone, a wide range of objects were collected, none of which had a secure context. These were mostly the kinds of material one would expect to find in agricultural topsoil, hinting at the origins if the clay-silt-loam material the Stone was buried with. These included broken ceramics, tiles and field drain pipes, glass, brick fragments and metal objects such as barbed wire and nails. Notable finds included two glass marbles, found separate from one another at the base of the Stone and wall, which we assume rolled there during play on the Stone, as well as two coins and a Red Cross medal. The small finds will all be cleaned and catalogued at the University of Glasgow, and the coins and medal conserved and analysed.

Samples: Samples were taken of the various paints found on the surface of the stone, as well as the melted plastic (initially found in 2015). These will be analysed using a portable XRF reader for chemical content and to identify their sources – in particular, it will be interesting to know what kind of paint Mann used. The location from which each sample was taken was marked on a plan of the site which will be included in the site archive.

| Sample Number | Material sampled |

| CS01 | Black melted plastic [sample also taken in 2015] |

| CS02 | Green-white paint from the largest cup-and-ring mark |

| CS03 | Red paint |

| CS04 | Yellow paint |

| CS05 | Red-white paint |

| CS06 | White paint |

Scanning and digital recording [Ferdinand Suamarez Smith]

The 3D scanning of the Cochno Stone represented one of the largest high-resolution digital recording projects of a cultural heritage artefact ever undertaken.

The process of digitally recording The Cochno Stone made use of several different techniques. The first method employed was aerial photogrammetry (using a DGI Phantom 4 drone) which was intended to capture the entirety of the form of the stone and provide a ‘map’ onto which higher-resolution data, capturing the detail of the surface, could be added to. Photogrammetry is a process by which 3D information is extracted from 2D photographic images. 2D images are made of the subject in a sequence, then a computer programme (in this case, Capturing Reality) recognises features from across the different images and triangulates the distance between them, placing points and building up a ‘point cloud’ of the surface (see Figure 12).

The data from the drone was better than expected and provided details of some of the graffiti, although not high enough resolution for the bench mark of what the ultimate end of the project is, the creation of a 1:1 facsimile. To achieve this end, we also gathered much higher resolution photographic data using a 50 megapixel Canon 5DS R on a horizontal linear guide with a ring flash attached. This was moved across the surface of the stone sequentially (using the same principle as described above), taking all due care to protect it using rubber feet on the tripods and foam shoes for the operators (see Figure 13).

The final stage of the process was laser scanning undertaken by a team from the Scottish Ten, using a Leica P40. Unlike photogrammetry, laser scanning measures distances by shooting light at the surface of the object then measuring the time in which it takes to return, thereby creating a point cloud of the surface. Like the drone, this was aimed at capturing the broad form of the stone rather than the micro level of detail. However, it has an additional advantage of superior accuracy and when used in tandem with the other techniques provides a basis for making the model geometrically accurate.

Laser scanning (Lyn Wilson)

A laser scan of the Cochno Stone was undertaken by Historic Environment Scotland’s Digital Documentation Team who digitally surveyed the site using a Leica P40 terrestrial laser scanner. Several scans were captured at a resolution of 3.1mm @10m around the perimeter of the exposed and cleaned bedrock and at key locations on the bedrock itself. Individual scans were registered using high definition targets. High resolution data capture resulted in a very dense point cloud. Data was registered using Leica Cyclone software to create one database. The data was exported to ASCII format (.ptx) and has since been transferred to Factum Foundation for further processing and integration with photogrammetric data within Reality Capture software (see Figure 16 for an early snapshot of results).

High-spy

The Historic Environment Scotland hi-spy unit also came on site, to take photographs of the Stone from above, in order to help enhance the NMRS records for the site.

Provisional results

At the time of writing this report, very little analysis of the digital, laser and photographic data has been carried out. It is possible though to offer some observations based on the archaeological work that was carried out on site, with the proviso that our understanding of these matters will greatly benefit from integration of the digital data in the coming months. Five significant phases of activity will be discussed: prehistoric rock-art, antiquarian recording, Ludovic Mann’s painting, modern graffiti and activities, and the burial of the Stone in 1965. It is hoped that these disparate elements will come together to offer a comprehensive and unique biography of the Cochno Stone over the past 4,000 years.

(1) Prehistoric rock-art

The revealing of the Cochno Stone simply reinforced the impression that the Stone is one of the outstanding examples of a cup-and-ring marked outcrop in northern Europe. The full range of motifs expected were discovered as well as some other markings that had not previously been noted.

Hints of phasing were identified with different depths of carving, overlapping symbols and differential weathering all pointing towards extended and multiple phases of carving on this rock, presumably in the third millennium BC (however, exactly when this was done in prehistory is something we will not be able to shed light on). Different methods of creating rock-art were also evident, something that we will also be able to explore, and this may help to shed light on whether some of the carvings (the footprints, cross-marked stone and some cup-and-ring marks) were modern additions.

These phenomena will be investigated as the data becomes available. Perhaps of special note is simply the variety and scale of the rock-art on the surface of the Cochno Stone, something that means that this was a significant and highly visible place in prehistory, as well as of remarkable note today. We also know from a ragged NE edge of the Stone that the rock-art may once have been more extensive; part of the stone seems to have been quarried away.

(2) Antiquarian recording

Only one drawing of the Cochno Stone has ever been undertaken, by Donnelly in the 1890s. This was later updated by Morris based on photography, but Morris did not actually see the Stone for himself (Figure 4). It is clear from out excavations that the scale on Morris’s drawings, which was added based on his own calculations, is flawed but also that the motifs are not arranged quite as shown on Donnelly’s drawing. The digital recording of the Cochno Stone will enable us to produce a definitive plan of the Stone, including motifs to scale and in the correct location. We will also be able to add carvings that had not previously been recognised, and rule out some that had been included by Morris and Donnelly that do not convince.

(3) Ludovic Mann intervention

The activities of Mann on the Cochno Stone in the 1930s are perhaps the strangest of his long and eccentric career (Ritchie 2002). Mann believed the Cochno Stone and other rock-art in the Glasgow area encoded cosmological and mathematical ideas and although he published little on the Cochno Stone itself, his activities in 1937 at the Stone were a significant and radical intervention in the story of this rock outcrop. There, he could demonstrate his theories in a dramatically tangible way on the surface of the Stone, painting everything that he regarded as an ancient symbol and adding an extensive ‘megalithic grid’ to the Stone (see Figure 3). As noted above, Mann believed that the Cochno Stone portrayed a legend associated with the prediction and ‘defeat’ of eclipses; ‘The sculpturings cover an area of 2000 sq. ft., and represent an extraordinary diversity of symbol pictures relating to important episodes in the heavens’ (Mann 1937b, 14).

Our excavations have shown that Mann used several colours of paint – red, blue, yellow, green and white were all identified (Figures 19) – and that each colour had a specific meaning, with yellow, red and blue used for different elements of his grid for instance. Some patches of the rock were almost black, which may either have been black paint, or discolouration at the damp fringes of the rock. Grid lines were apparent across much of the stone, even when coloured paint was not evident, and these ghostly lines suggest perhaps that Mann incised his grid lightly onto the stone surface to ensure the accuracy of his work.

We also know that he painted spirals and symbols that were either natural variations in the rock surface, or modern graffiti. And he appears to have drawn in at least one circle of his own making (Figure 20). Unfortunately, we were unable to find evidence (at least through visual observation) of the ‘ruler’ like markings made on the northern edge of the Stone (Figure 21). Samples were taken of the paint (see samples list above) for analysis and it is remarkable that the paint has survived, especially as it was exposed to the elements for 28 years before burial.

Mann’s painting of the Stone could be viewed as an act of vandalism that simply encouraged further damage to the Stone. It could also be considered an incredibly creative act, that entailed a huge amount of work and craft. Perhaps we should see his work in both lights. In the next phase of the Project we intent to explore Mann’s theories about the Stone and the work he did there, with the addition of some unexpected technicolour.

(4) Modern graffiti and damage

One of the main reasons that the Cochno Stone was buried in 1965 was the profusion of graffiti and we found ample examples of this across the Cochno Stone, with over 50 individual instances of graffiti found from full names, to initials. These ranged from careful, almost bookplate writing of full names, to untidily scrawled and almost illegible words. Some of these names and initials had dates associated with them, ranging from the 1930s right up to 1965. A few pieces of writing had additional flourishes, such as spirals beneath the writing (mistaken as prehistoric spirals by Mann) or boxes around the name.

The graffiti appears to be concentrated in the lower southern zones of the Cochno Stone, although some also is evident amidst rock-art towards the high point of the rock notably the DOCHERTY graffiti found in 2015 (Figure 5). Writing occurs in various orientations although strong preferences and clusters of graffiti may well relate to episodes of writing on the Stone e.g. by a group of individuals at the same time facing to the east. Dates in 1964 and 1965 are commonplace, suggesting that an upsurge in vandalism played a role in the burial of the Stone around this time. Several cup-and-ring marks are pecked in appearance and irregular, and may be modern copies; it is hoped that analysis of the data will help identify such instances (see Figure 16 for instance). We also identified an area of the Stone that appeared to have been burned perhaps by a fire set on the surface (Figure 25); this may be related to the burnt plastic we found nearby stuck to the stone (see Brophy 2015), and it is presumed this happened near the time the Stone was buried.

It is hoped that some of the writers of the graffiti can be identified so we can interview them and find out their motivations and means of creating the graffiti, which will help us make sense of the social history of what was known locally as the Druid’s Stone. A study of the graffiti will be undertaken for an Undergraduate dissertation at University of Glasgow by Alison Douglas.

(5) Burial of the Stone in 1965

Little more light was shed on the burial of the Stone during the 2016 excavations. The depth of soil on the Stone varied considerably from c0.5m at the highest point of the Stone to up to 0.8m deep at the lower, southern extent of the walled zone. No damage due to the wall collapse was evident, but upper courses of the wall had clearly been thrown into the clay-soil matrix as the Stone was being buried. It may well be more can be learned about this event by continued archive research, as well as collecting the oral history of the Stone.

Conclusion and next phase of the project

The uncovering of the Cochno Stone for 10 days in September 2016 was a great success, with extensive media coverage but also great local interest in the project. We were also able to engage with both local schools.

In archaeological terms, we succeeded in removing the soil from the top of the stone without causing additional damage to it, and we carried out all the recording work that we wanted to. This has given us an incredibly powerful dataset to work with going forward into the future, with the intention of raising funds to create an exact replica (or facsimile) of the Cochno Stone amongst our plans although we can also use the data to study the surface of the stone, create 3D visualisations of the Stone and create materials for information boards, exhibitions and social media. The data gathered also gives us a tremendous opportunity to engage with the local community in Faifley and Hardgate, to find out stories and memories of the Cochno Stone, many of which were shared with us during the excavations.

The Cochno Stone has been buried for the second time in 51 years, but its future remains open for debate and discussion. It is hoped the Revealing the Cochno Stone project has been a catalyst for an exciting future of the stone whether it remains buried or not.

Acknowledgements

The excavation would not have been possible without the permission of the landowners, Mrs Elaine Marks and her son Gary, and West Dunbartonshire Council, and we are very grateful that we could carry out this work. Our main point of contact with the Council was Donald Petrie, whose help and support throughout was very much appreciated; thanks also to David Allen. We also received permission from HES in the form of Scheduled Monument Consent (SMC) and we are grateful for their advice in navigating our way through this process successfully as well as manage what was a unique project, we would like to thank HES’s John Raven and Stephen Gordon. Richard Salmon was on site at all times to advice on working on the surface of the Cochno Stone, and this was greatly appreciated.

Revealing the Cochno Stone was funded by the Factum Foundation and the University of Glasgow.

Many people worked on the site and we would like to thank them all. The team of archaeology students from University of Glasgow was supervised by Helen Green. The team included Aurume Bockute, Liam Devlin, Alison Douglas, Hannah Dunn, Jo Edwards, Taryn Gouck, Anemay Jack (Aberdeen University), Jools Maxwell, Scott McCreadie, Joe Morrison, Katherine Price, Jennifer Rees, Elizabeth Robertson and Lauren Welsh. Alison Douglas has also carried out some initial analysis of the modern graffiti. Thanks especially to Alison, Taryn, Lauren and Jools for their help with the school visits. The Factum team would like to thank Dani Trew and Tom Don, Lucie Salmon, Jules Salmon, and Alison and Fergus Leckie for all their help. The machine work on site was carried out brilliantly by the digger driver Davie and banksman Danny; thanks also to George McKenzie of Greenlight Environmental for help and advice throughout the project.

We would also like to thank the teams from Scottish Ten and the History Channel for helping to record the stone and document the project. Figure 16 appears with permission of HES.

Many other individuals played a vital role in the project. Danny Docherty helped on site, and was also instrumental in arranging for the fire service to help us out. Cleaning of the Stone was undertaken by the Clydebank Fire Brigade and we are very grateful for their support. Friends in the media were on site frequently documenting what we were doing, notably Huw Williams and John Devlin (who kindly allowed us to reproduce Figure 17), and the media coverage was organised by Jane Chilton. Thanks also to Gil Paterson MSP for being supportive and for giving the project a positive mention in the Scottish Parliament. And many thanks to Grahame Gardner who visited us several times and was kind enough to conduct the pagan ceremony before the Stone was reburied. Thanks as well to Anne Teather who drove almost 500 miles to see us!

Finally, we would like to thank all the people who visited the Cochno Stone, and who treated the Stone with respect while it was open and exposed. Their enthusiasm, support and stories inspired us. Special mention here to Owen, May Miles Thomas who started it all, and to Stevie, the guardian of the Stone.

Many people worked on the site and we would like to thank them all. The team of archaeology students from University of Glasgow was supervised by Helen Green. The team included Aurume Bockute, Liam Devlin, Alison Douglas, Hannah Dunn, Jo Edwards, Taryn Gouck, Anemay Jack, Jools Maxwell, Scott McCreadie, Joe Morrison, Katherine Price, Jennifer Rees, Elizabeth Robertson and Lauren Welsh. Alison Douglas has also carried out some initial analysis of the modern graffiti.Thanks especially to Alison, Taryn, Lauren and Jools for their help with the school visits.

Many other individuals played a vital role in the project. Danny Docherty helped out on site, and was also instrumental in arranging for the fire service to help us out. Cleaning of the Stone was undertaken by the Clydebank Fire Brigade and we are very grateful for their support. Friends in the media were on site frequently documenting what we were doing, notably Huw Williams and John Devlin, and the media coverage was organised by Jane Chilton. Cleating the bulk of the soil on top of the Cochno Stone was the machining team who did a great job. Thanks also to Gil Paterson MSP for being supportive and for giving the project a positive mention in the Scottish Parliament. And many thanks to Grahame Gardner who visited us several times and was kind enough to conduct the pagan ceremony before the Stone was reburied. Thanks as well to Anne Teather who drove almost 500 miles to see us!

Finally, we would like to thank all the people who visited the Cochno Stone, and who treated the Stone with respect while it was open and exposed. Their enthusiasm, support and stories inspired us. Special mention here to May Miles Thomas who started it all, and to Stevie, the guardian of the Stone.

References

2015 Cochno Stone report (aka Brophy 2015)

Cochno Stone CANMORE entry

Bruce, J. 1896 Notice of remarkable groups of archaic sculpturings in Dumbartonshire and Stirlingshire, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 30, 205-9.

Harvey, J 1889 Notes on some undescribed cup-marked rocks at Duntocher, Dumbartonshire, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 23, 130-7.

MacKie, E. & Davis, A. 1988-89 New light on Neolithic rock carving. The petroglyphs at Greenland (Auchentorlie), Dunbartonshire. Glasgow Archaeological Journal 15, 125-55.

Mann, L M 1937a An appeal to the nation: the ‘Druids’ temple near Glasgow: a magnificent, unique and very ancient shrine in imminent danger of destruction. London & Glasgow.

Mann, L M 1937b The Druid Temple Explained. London & Glasgow. [4th edn, enlarged & illustrated, 1939.]

Morris, R W B 1981 The prehistoric rock-art of southern Scotland (except Argyll and Galloway), Oxford: BAR British Series 86.

Ritchie, G 2002 Ludovic MacLellan Mann (1869-1955): ‘the eminent archaeologist’, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 132, 43-64.

Great work, and I’m enjoying reading about the progress on this site and the insights it will give. Comparing your Figure 16 (Laser Scan) shows clearly that your Figure 3 (Photo of Ludovic Mann kneeling on the carvings) is inverted – perhaps it was originally on a glass plate? If you confirm this I’ll let Canmore know. Other published photos from 1937 may be inverted also.

Hi, sorry for not replying sooner. Thanks for this observation, you are right! This has made sense of the photo as we try to piece together all the information we have to create a definitive plan of the stone. Please do let CANMORE know!

Kenny

Thanks for this update. I thoroughly enjoy your blog in all its facets (I’m fond of urban fakery as a kind of eternal truth; I am an architect by training!), and am very happy to share the excitement around this monumental undertaking.

Hi, that’s very kind of you. I’ll continue to use the blog and twitter to provide updates on the project.

Kenny

I used live in a street in the Faifley called Cluny avenue (no longer there), but as kid in the 50/60s we used to play on these stones all the time, especially in the summer. Strange thing is that I seem to recall that there was a large stone and a smaller one; the smaller having less markings. I could be wrong, it was a lifetime ago.

Hi Bill, quite a few of our visitors told us they remembered another smaller stone in the area with rock-art so we can try to find this. It might also have been the stone outcrop outside the walled area that you are remembering right enough, as although this is the same lump of stone as Cochno, it looks like a separate rock. Can you remember what you were doing when you were playing on the stone? We found some marbles during our excavation.

Kenny

Hi, I noticed on fig 7 by the chap in the green jacket, by his knee appears to be a round white-sh stone? Above this stone on the wall bank is another unusual stone. My question, were these stones recorded?

Question 2, fig 10 The Blessing, looks like a birds ‘PHOENIX’ head negative on the stone, could be drying of the stone that’s giving this impression.

I’m fully enjoying the stones journey.

Well done to all involved and thank you.

Dawn McAlister

Film crew for the History Channel were present during the uncovering. They said the programme would be aired in 2017.

I believe the History Channel team are editing the programme just now for broadcast later this year. I think the show is part of a series called Impossible Projects.

Kenny

YouTube has the relevant episode. I could only find one that is in Hindi with English subtitles, but it’s fine for viewing.

Project Impossible – Unsolved Mysteries, Series 1 Episode 7 on

The History Channel.

Main part starts around 23:38 time.

Hello Ken, if you manage to get a replica made can you guarantee that the symbols will have the same orientations as the original ones? I ask this because the standing stones at Kintraw and at Nether Largie, when re-erected after they had fallen, were aligned in the wrong directions.